Effusus Over Nothing (Solo Show)

Patriothall, Edinburgh

Gallery One

(Images of Gallery Two below)Text by

Kat Cutler-MacKenzie

Emma Hislop presents an ensemble of cast, forged and found pieces in Effusus Over Nothing, drawing upon her

material knowledge of glass, metals and ceramics to explore the cultural and ecological implications of the soft

rush (named juncus effusus in Latin). Juncus Effusus is associated with infestation for many farmers, who

struggle to remove the rapid spreading plant from their land, whilst manufacturers often find the process

required to separate its soft inner from its woody stem too time consuming to be of use. Yet, in many cultures,

the soft rush has acted — and still acts — as a primary making material, including in the production of hats,

baskets, candle wicks, tatami mats and religious symbols. As such, Hislop’s work is, in one sense, a ‘fuss over

nothing’, after which the exhibition takes its name. Juncus effusus is a common plant whose stubborn material

rejects the fast pace of capitalist production — its profit value is near zero. But in Hislop’s work, the sweet

smelling plant is (re)valorised, opening dialogues with its past(s) as well as with its future(s).

Gallery Two

–––––––

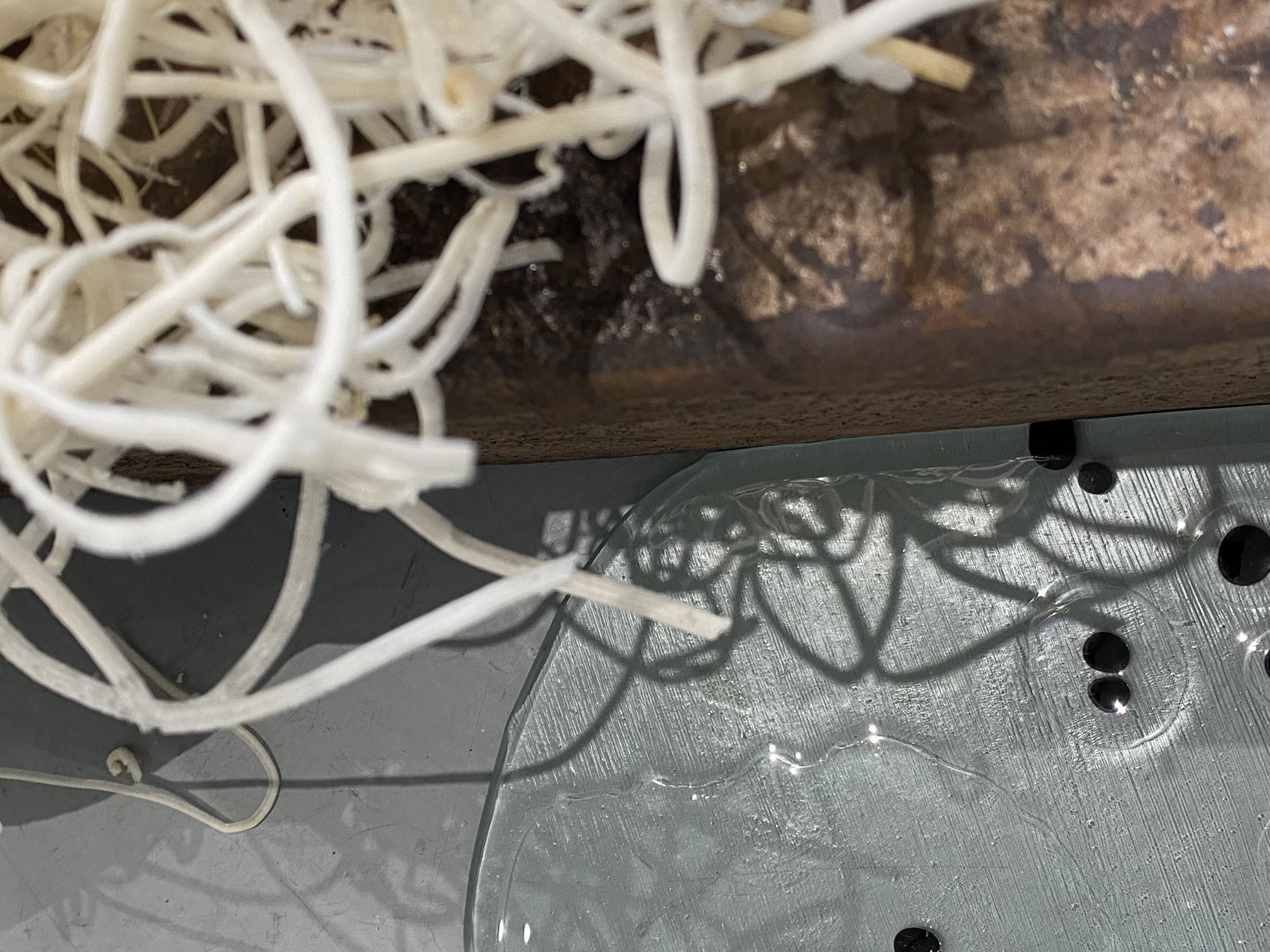

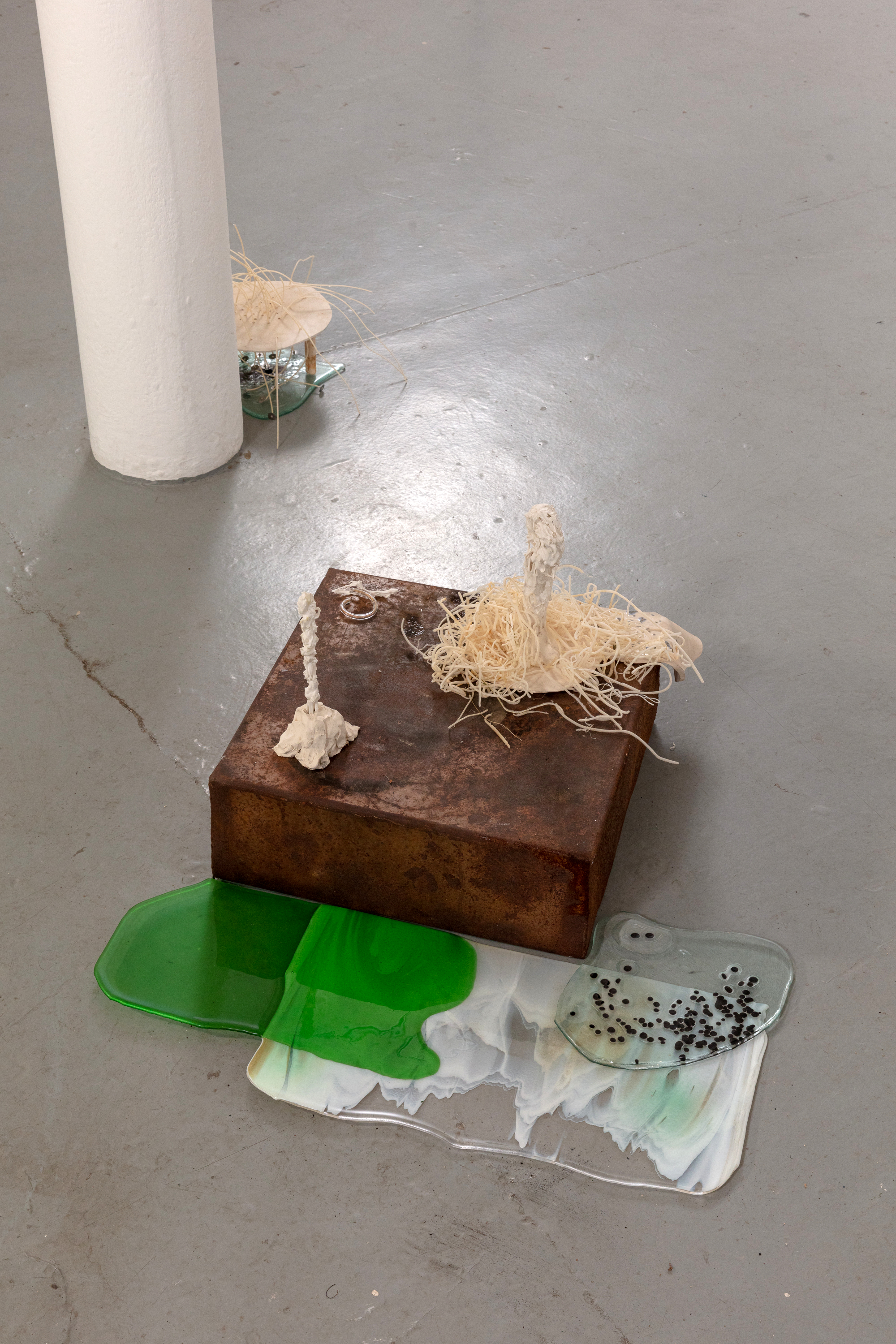

In Effusus Over Nothing you encounter a series of apparitions, islands and ponds. In the second gallery, glass pools, specked with black, like polluted waters. They look like petri dishes from afar, echoing Hislop’s interest in laboratory apparatus. In Effusus Over Nothing Hislop uses these islands to speak to the purifying properties of the plant, whose roots support large numbers of bacteria that aid water filtration, and whose dense mass prevents detritus (such as roadside plastics) from entering bodies of water in which the plant grows. These pools metamorphose between liquid, glass and light. For Hislop this is alchemy: concerned with the transmutation of matter, involving a seemingly magical process of transformation, creation, or combination.

For this exhibition Hislop has undertaken many alchemical processes, including the casting of a rushlight holder from molten iron. Here, as in her other hand-modelled objects, the finger marked surface reveals the material transformations that the holder has undergone. An emphasis on (un)finished surfaces is a key part of Hislop’s work, serving to capture the movement between forms and matter through which her sculptures are borne. In this vein, alongside the iron holder are a series of smoke drawings in which the artist has caught shapes and shadows created by the burning of the rushlight — a wick made by immersing the soft, sponge-like centre of the plant in tallow. The drawings are frenetic and wisp and fume. They are atmospheric and evoke, for Hislop as for author Washington Irving, the “mischievous powers of the air”, the product of “a feeble yellow ray, dimly illumining the chamber, and making uncouth shapes and shadows on the walls” (Dolph Heyliger, 1822). From Hislop’s drawings you can imagine the misty, murky light emitted by the candle when burnt.

In this space of the rush it is hard to breathe. The air is polluted, the water is pocked, then a glowing bronze canister appears. The accumulation of waterside environments, smoke drawings and a gas canister fixed to its mask by a sweet smelling rope of rush creates a compelling image. However, it also brings to light the interconnected way in which Hislop and the rush have learnt to make: together, by relation, as a web. As Hislop states: “it’s only an ecology that keeps them [juncus effusus] alive”, which is mimicked in her choice of installation. Collected, accumulated, assembled, combined, Hislop takes a quasi-museological approach to the runt of the rush family tree in Effusus Over Nothing, exploring the plant in a diversity of soft, spiked, sweet and bitter forms and uses.

The effect of this exhibition is, for Hislop, to show how alternate forms of production and of living with our local ecologies exist within the rush. A series of material experiments and fabrications, Effusus Over Nothing is a laboratory, pertaining to the future relationship — by way of past techniques and usages — between the human hand and the body of the soft rush.